A Long, Cold Winter

- Piper

- Jan 12, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2022

By May Davidson

Trudging the last half-mile of steep uphill while pulling the sled and groceries was less fun. There were times when keeping our footing on the ice was such a challenge that we would arrive breathless at the cabin to find that some of the grocery sacks had toppled and several items were missing. I would light the stove while Jim went back down the hill for a loaf of bread here and a bunch of carrots there. It was usually eight o’clock at the earliest before we had supper ready. Breakfast at four-thirty that morning seemed a long time ago.

It didn’t matter because we had to go to bed early to meet the next day’s schedule. We didn’t have a radio and reading was difficult by the dim light of our kerosene lamps. We had one large mantle lamp that was brighter than the others, but we learned that trim- ming wicks for an even flame was an essential skill. One evening Jim fell asleep with a book in his hand, and I was so absorbed in a novel I didn’t realize that the lamp was smoking until I stood up and could barely see through the black cloud. Jim’s nostrils were outlined in black soot, and I had a dark greasy mustache. This was a minor inconvenience compared to the smoky film that lay on the walls and other objects in the cabin. The cleanup served as a lesson in lamp care that remains with me still.

There wasn’t much time for entertainment, but we needed even a small diversion. We shared a mutual passion for cats, and one weekend Jim came home from an errand and handed me a half-grown scrawny, black cat with white nose, chest, and paws. A lobsterman friend, Alfie Butler, had been willing to part with one of his dozen or so kitties. Joe’s name had already been bestowed upon him. He had long legs, knobby knees, and a long stringy tail. He was a slouching adolescent, but he had a sweet face and charming disposition.

He was also a thief.

I made a custard pie one Saturday morning and left it on the counter to cool while we went out to cut firewood. It never occurred to me that Joe could be interested in anything but fish, meat, or milk. When we got home at lunchtime Joe was on his haunches beside the pie contentedly washing his face. His eyes were happy slits and bits of custard dripped from his whiskers. It appeared that he had eaten from the center outward, as all that remained was a narrow circle of custard around the edge. I would have been glad to give him a piece if he had left us some too, but you can neither reason with nor truly discipline cats, and we didn’t try. My pies cooled behind closed doors after that.

We had jobs, but winter is the wrong time to start living in a rough cabin if one has a choice of spring and can enjoy the gentle summer months to make improvements. Fighting snow, cold, and ice enlarges each task. Our bathroom was the great outdoors. There were miles of forest around us with nobody in it, so privacy was no concern. The weather was.

Unlike many Maine people without indoor plumbing I could not bring myself to cope with a “slop jar” or chamber pot. I’d heard of too many accidents, and cleaning up without running water was unappealing. A couple we knew followed the old tradition. Nettie and Harold both worked away from home daily. While she washed the break- fast dishes, he emptied the “slops.” They were running late one morning, and the outdoors was glittering after an all-night ice storm. Harold, slops in hand, moved hastily through the orchard to the wooded dump- ing spot. On the way he slipped, hitting an apple tree with his delicately balanced cargo, which emptied all over him on his way to the ground. It was a long while before he

was fit to go to work that morning. Stories such as these are immensely funny when they happen to someone else, but my sense of humor was limited when I pictured such a mishap befalling either of us.

The great outdoors remained our bath- room until one cold sunny weekend when Jim built us an outhouse. I thought it was beautiful—bright pine boards, a roof that matched the cabin, and all just a comfort- able distance away.

Jim built it so that the front was on a ledge, and the back was enclosed in an overhang beyond the edge of the ledge for easy cleanout. It was beside a massive pine tree whose branches hung just above the door softly framing it. Inside was a neat little bench with a hinged cover and a small bag of lime. Following the pattern of the old outhouse at my parents’ home, I tacked colorful calendar pictures around the inside walls.

Time proved that, outhouse or not, we still fell victim to the weather. The hand- some snow-laden pine branches melted all over the doorway during the day causing the door to freeze shut at night. We couldn’t afford siding and melting snow found its way through cracks in the walls and froze the seat cover to the bench. It was useless to visit the outhouse without a screwdriver to pry open the door and loosen the frozen seat. We kept this handy item hanging by the kitchen door.

Because of the overhang from the ledge, the distance from bench to ground below was considerable, and the enclosure acted like a chimney—the updraft was both frigid and forceful. Conversely, in summer it was a pleasant place and the wind soughing in the giant pine was soothing.

Late December snow and ice were nothing compared to the frigid polar air that clutched us in January and February. We learned the meaning of cold—its length, breadth, and intensity. Its glacial, boreal, skin-whitening, blood-slushing, bone-crunching, gut-freez- ing relentless eternity. In those months, a zero-degree day seemed toasty warm. Temperatures dipped to fifteen and twenty below zero, several times hitting forty below. We never had central heat in the old inn-farmhouse where I grew up, so I knew what it was like to go to bed with two hot water bottles, and three sweaters on top of a flannel nightgown, and still shudder under several blankets and quilts. But lying in a log cabin with half of it open to the roof was even colder.

Our fireplace was lovely, but threw heat barely three feet from itself, and most of that was lost to the high ceiling.

Our kitchen stove was a malevolent beast. It provided heat in the kitchen only if we fed it with wood nonstop. It would hold a glorious coal fire, glowing with blue flame hovering over the fiery coals, but the stove guarded this treasure jealously and no heat escaped its firebox. It wouldn’t boil water on its surface. Our cat, Joe, would creep into the oven, left open in the wan hope of some heat emanating from it, and snuggle against the firebox. One morning when I sleepily arrived in the kitchen, I shut the oven door hoping to build up enough heat to warm some breakfast biscuits. Joe’s black-and -white coat matched the mottled interior of the oven and I didn’t notice him curled in its depth. Later when I checked for a buildup of heat, he shot out over my shoulder in a shrieking streak, legs, jaw, and eyes opened wide. Since it happened to be a coal fire, he was not overheated, but was very alarmed at the narrow, dark confinement. Thereafter I explored the oven before closing the door.

I found it a pleasure to go to work each day just to be warm. I loved being a tele- phone operator anyway. Jim’s work was outdoors and the action of woodcutting all day kept him warm except when every blow of the ax sent snow from the laden branches down his back. At noon he toasted his sandwiches on the end of a stick over an open brush-burning fire.

By midwinter it seemed that cabin would never be warm again. The sap in the green logs froze and exploded in vertical cracks. This “checking” is a natural drying process. The cracks are not deep and do no structural harm. But the explosion when they occur is like a rifle being fired past your ear. We rarely slept through the night, the noise was so sharp.

As they dried, the logs shrank just enough to let the caulking drop out. Daily we found places in the walls that afforded us an outdoor view and we walked around with a hammer and caulking iron to fill them.

Water was another challenge. The well near the old farm foundation was six feet in diameter and a third full of water when winter arrived. It iced over in December, but with a long stout pole we kept punching a hole large enough to lower a bucket through on the end of a rope. When January’s ice age came along, Jim climbed down the rock walls and chopped a hole through a foot of ice with an ax to give us access, but we were only home during daylight on weekends and it was too time-consuming to spend an hour each night and morning chopping a water hole, so I brought water home in small jugs from the telephone company. I still can’t believe how little water two people can get by on if necessary.

Because the kitchen stove wouldn’t heat the room with coal, and somebody had to tend it constantly to keep its maw filled with wood, the cabin always felt like an ice cave when we came home at night.

Weekends were mostly devoted to cutting the following winter’s wood supply. There was enough hardwood on our land to last us for several winters. Although I could split wood with an ax, I didn’t have what it took to chop down a tree. With several experienced swings Jim could fell a tree in any direction he wished, and together we cut them into four-foot lengths with a crosscut saw. I learned from Jim not to push the saw into the wood but to guide it properly while letting it ride into the log by its own weight.

Jim kept it sharp and I enjoyed the teamwork as we pulled it back and forth and watched it sink into a piece of icy oak, spattering the snow with pink, bittersweet smelling sawdust. The best of our wood was near the sea. Salty ice cakes glistened in the thin winter sunlight, and the black spruce crests of Keene’s Neck and Hog Island lay against the pale winter sky. Whenever I think my feet are cold, I remember a day on our woodlot and how cold it is possible for feet to become without actually freezing.

We were saving money for an inboard engine powerboat in spring, so we cut every corner possible. My winter boots had given up and the most complete footwear I owned in addition to what I wore to work was a pair of sneakers. Jim had two pair of Army boots from his service, but his size elevens wouldn’t fit my five-and-a-halfs. I still love the light-footed feeling of sneakers and wear them year-round even now—but by choice. They aren’t for woodcutting at below zero temperatures. Canvas seems to conduct cold right to the inner workings of one’s feet. I didn’t give in that day, but I wanted to go home and stick my feet in that lukewarm oven so badly, I didn’t care if we crystallized next winter without the firewood that would be cut this day.

The depths of winter also provided splendid beauty at times. Moonlight on the pine-encircled frozen cove made it look like a great tray of glittering sugar, silvery frost crystals floating like winter fireflies in the brittle air.

Some night I hope to see the northern lights again as they were on a February night when we walked the icy road to the cabin. They flashed and scintillated in ever-changing curtains turning from blue-white to brilliant red, pinks, and yellows. The veils then drew together and hung in a complete and surrounding circle from a fiery dome straight above. Still shimmering and blazing they began to crackle and then to roar, the sound swelling to crescendos that made us think the world might be approaching an end. Although we were awestruck it was too beautiful to be frightening. We stood in the center of this magnificent scene for nearly an hour forgetting the cold.

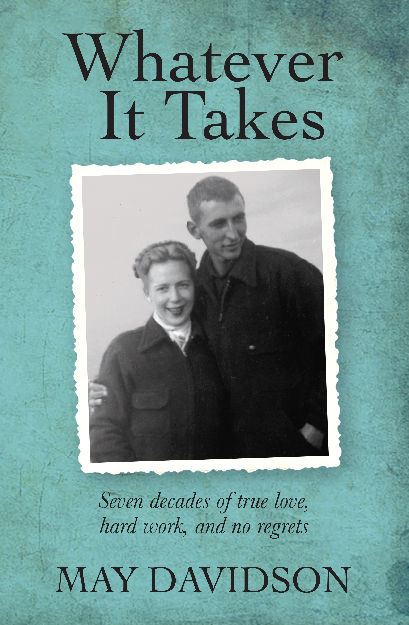

May Banis was born in Damariscotta in 1929 and raised in Bremen, where her parents owned and operated The Mayfair House on Greenland Cove. She graduated from Lincoln Academy in 1947 and married James Davidson in October of 1948. May’s parents carved out five acres of land from their property and gave it to the newlyweds as a wedding present. In 1949, May worked at her parents’ inn and Jim went lobster fishing in a small dory to make enough money to build a primitive log cabin in the woods. The cabin had no running water, no electricity, and no good access road. The couple moved into their new home in late 1949 and in the this excerpt from her book, Whatever it Takes, May recalls that first winter.